By

REZEKNE,

Latvia — On a continent of fractured loyalties, a kaleidoscope of separatist

passions extending from Scotland to eastern Ukraine, Piters Locs, the 70-year-old champion of an obscure

and, at least officially, nonexistent language, has a particularly esoteric

cause.

“We

are a separate people,” he said, showing visitors around the private museum he

built to celebrate the language and literature of Latgale, a sparsely populated

and impoverished region of lakes, forests and abandoned Soviet-era factories

along Latvia’s eastern border with Russia.

While

Mr. Locs insists that he has no desire to see the area break away from already

tiny Latvia, such passion for Latgale’s language and its distinct

identity helps explain why Russian nationalists see this region — about a

quarter of the country — as fertile ground for their machinations to divide and

weaken NATO’s easternmost fringe.

Only

about 100,000 people actually speak Latgalian. The authorities in Riga,

Latvia’s capital, consider it a dialect of Latvian, not a separate language,

and nobody is punished for speaking it.

But

complaints that the region’s culture, heavily influenced by Russia, is under threat have been taken up with gusto by

pro-Russian groups, fueling suspicion that they work as a front for Moscow.

In

a recent article urging Russia to undertake a “preventive occupation” of this

and two other Baltic nations, all of them NATO members, Rostislav Ishchenko, a

political analyst close to influential nationalist figures in Moscow, asserted

that Latgale’s separate identity could help open the way for a “revision” of

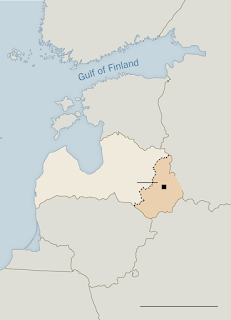

Baltic borders. A map accompanying the

article showed Latgale as a separate entity taking up the entire length of what

is now Latvia’s border with Russia.

Such

a scenario would mean a Baltic replay of events last year in Ukraine, where pro-Russian separatists and so-called green

men — Russian soldiers in uniforms stripped of insignia — seized Crimea and

then territory along Ukraine’s border with Russia.

Much

the same strategy has been promoted in a recent series of mysterious online

appeals calling for the establishment of a “Latgalian People’s Republic,” a

Latvian version of the Donetsk People’s Republic supported by Russia in

Ukraine.

Latvia’s

Security Police, the domestic intelligence agency, have struggled to trace the

source of the appeals but believe they originated in Russia.

“They

seem to be some kind of provocation to test how we would react,” said a

security agency official, who asked not to be identified because of the

delicacy of the issue. He said there were no signs of separatist fervor in

Latgale itself and described the Latgalian People’s Republic as an “artificial

creation by outsiders.”

Eastern

Ukraine also displayed no separatist fervor until Russian-backedgunmen

in March 2014 seized government buildings in Donetsk, silenced local

supporters of Ukraine’s central government and, aided by Russian state

television, mobilized a previously passive population to the separatist cause.

“The

crux of the matter is that you have to be in charge, in control. Once you give

the initiative to the other side, you are lost,” said Janis Sarts, the state

secretary for Latvia’s Defense Ministry. He noted that regular rotations of

NATO troops and aircraft through Latvia had sent a firm message to Moscow that

“the risks would be tremendous” if it tried to copy its Ukrainian playbook in

the Baltics.

In

a blunt, if theatrical, warning to any would-be troublemakers, Latvian

soldiers, border troops and the local police held a joint exercise last month

here in Rezekne, the Latgale region’s historical and cultural capital.

With

shouts of “hands in the air” as a military helicopter clattered overhead, a

special forces unit of Latvia’s border troops stormed the district council

building to confront mock “terrorists” who had seized the premises.

The

raid lasted just a few minutes and ended with the rabble being dragged from the

building and then dumped into a military truck.

If

the whole operation had echoes of the conflict in Ukraine, down to the grimy

tracksuits of the make-believe insurgents, it was no mistake. Rather, it was

meant to send a clear signal that “we are ready, and it is not so easy to do

illegal things,” said Brig. Gen. Leonids Kalnins, the commander of Latvia’s

National Guard.

The

exercise was held in the center of town, a few yards from a bronze statue

called United for Latvia, a monument to national unity that, over the decades,

has been more an emblem of the tenuousness of power in these parts. Erected in

1939 during a short-lived Latvian republic, it was taken down when the Soviet

Union annexed the Baltics in 1940, put back up in 1943 during the Nazi

occupation, removed again in 1950 after Moscow regained control, then put back

up again in 1992 after Latvia regained its independence.

Edgars

Rinkevics, Latvia’s minister of foreign affairs, dismissed the online campaign

for Latgalian independence as the work of “Internet hooligans,” but said it was

unclear whether they were “lone wolves” or part of a broader strategy to

“create an atmosphere of uncertainty.”

Moscow,

he added, finds it “very difficult psychologically” to accept that Baltic lands

it ruled until the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union are now firmly entrenched

in NATO and the European Union.

Russia,

Mr. Rinkevics said, poses “no imminent military threat” to Latvia but “will

push as far as it can” as part of a “revisionist project” to reshape the

post-Cold War order.

The Security Police have been tracking what they view as Russian-inspired

mischief-making in Latgale for years, especially since the publication in 2012

of “Latgale: In Search of

Another Life,” a

lengthy book written in Russian by co-authors who include Aleksandr

Gaponenko, the

Russian-speaking head of the Institute of European Studies, a Riga-based outfit

that security officials consider a front organization for Moscow.

Mr.

Gaponenko denied advocating Latgalian independence and accused the authorities

of fabricating the issue to whip up hostility toward Russia and excuse the

presence of American troops in Latvia.

Others, such as

Vladimir Linderman, the leader of the Latvian branch of Russia’s National

Bolshevik Party, a belligerent fringe group, claim that they do not want Russia

to grab Latgale and that they instead champion “autonomy.”

Getting power

for Latgale to set its own course will be difficult, he said, as “the people

who are ready to struggle have all left,” including many who went to seek jobs

in Western Europe and Riga, but also about a half-dozen he knew who had gone to

join separatist fighters in eastern Ukraine.

Though there are

no reliable opinion polls to gauge Latgale’s discontent, the region has many

reasons to feel separate, set apart by its religion — Catholicism instead of

the Lutheranism favored elsewhere in Latvia — its dying language and its

distinct, often nightmarish history.

The biggest

religion in Rezekne was Judaism until last century, when it was obliterated by

the Nazis, with help from Latvian police officers. The Jewish community — 70

percent of the local population in 1885 — now has just 52 members in a town of

more than 30,000 people.

“We are the

smallest community but have the biggest graveyard,” said Lev Sukhobokov, a

local Jewish leader, showing a reporter the spot where Germans and their

Latvian helpers staged a mass killing of Rezekne’s Jews in 1941.

Today, in

Daugavpils, Latgale’s biggest city, almost half the population is Russian.

Russians are not quite so numerous in Rezekne, but in a 2003 referendum, 55

percent of its voters opposed joining the European Union. In the country over all, 67.5 percent voted in favor of joining.

Rezekne also

bucked the national trend in a 2012 referendum on whether to make Russian an

official state language, voting in favor of a move that was overwhelmingly

rejected by the country as a whole.

The European

Union has financed a huge new concert hall and other projects, but the

Russian-speaking mayor, Aleksandrs Bartasevics, denounces European sanctions

against Russia, trusts Russian television more than Latvia’s mostly

pro-European news outlets and worries that NATO will bring trouble, not

security.

“What frightens

me most is that American soldiers and tanks will appear,” the mayor said. “That

is a signal of where the next conflict is happening.”

No comments:

Post a Comment